The widely accepted “healthy” ratio, particularly at companies with mature SRE practices like Google, is one SRE for every 10 Software Engineers (SWEs) (a 1:10 ratio). However, this ratio can vary significantly based on an organization’s specific needs, size, and the maturity of its automation and tooling.

– Gemini

For the past 10+ years working as SRE, most of it while in short-staffed squads in late-stage start-ups, the SRE:SWE ratio was nowhere near the 1:10 “gold standard”. A more accurate ratio in my experience is 1:30 - 1:40, and in this setting, saying things can get pretty busy is a bit of an understatement.

Working in highly constrained environments such as these does not come without its challenges, both cultural and technical. For every task you choose to work on, there are like ten others you need to put on hold, all while doing your best not to become a bottleneck for the entire organization.

But this is not the only constraint I’m used to. The other one is cost efficiency; here, offloading everything to expensive SaaS offerings is not an option, so we usually resort to self-hosting, tuning and stitching open source tools for our needs. Deploying a new tool is also something we do not take lightly, as each new tool could drag the team down into an operational hell, so we tend to bet on boring/flexible tools as opposed to over-specialized ones.

The Problem

While working on improving the operational and security maturity for the organization, we wanted to review and reduce direct permissions to the production environment, and one possibility was to use Terraform, which the SRE team already used and was familiar with. But how could we provide other teams the same tools we used1 in a way that was safe, within the established best practices, and most importantly, did not require the SRE team to review each and every Terraform PR?

Here’s a non-exhaustive list of things we were after:

- Enforcing consistent naming conventions2

- Ensuring resources had the correct labels for proper ownership and cost tracking

- Blocking dangerous operations (i.e. database/bucket deletion)

- Ensuring durability best practices (i.e. enforcing backups for production databases)

- Forcing security best practices (i.e. requiring TLS for DB instances)

At the same time, we didn’t want to always block things that went off the standard path. Some of these requirements were created after critical infrastructure was already in place, so these needed to be supported.

Other reason is that sometimes the team might have a good reason to create a publicly exposed bucket or disabling authentication for a Redis instance, etc, so a workflow for approving these changes was also needed.

The simplest (and cheapest) solution at the time was to codify these practices as OPA policies and enable conftest in our Atlantis pipelines. The workflow is not perfect, but it gets the job done.

With these policies in place, teams could own their Terraform workflows and apply changes to production without waiting on the SRE for changes that were considered harmless, deeply reducing the PR review load on the team.3

Other options we considered:

- GCP Organization Policies: We use Google Cloud for most things, but use specific services from other public clouds as well (AWS, Azure), so a cloud-specific solution was not an option; higher than desired friction in case of policy violations / break glass scenarios.

- Terraform Cloud + Sentinel: Recent history of hostile decisions against the community; pricing model based on resources under management.

- Spacelift and Env0: Too expensive for the number of users and features (single sign-on, RBAC, etc) we required.

A Simple Example

We had great success in using GenAI for generating both policies and tests for various cases, but to get you started, here’s a policy I got from our library:

|

|

As our collection of policies grew, we ended up with a few extra packages for reusing some common behavior, such as:

|

|

Linting and Testing

I recommend using Regal to avoid common mistakes and help you write more idiomatic Rego code:

% regal lint .

3 files linted. No violations found.It’s also important to write tests for your policies to accelerate the feedback loop when introducing new policies while catching regressions early.

Here’s an example test suite for that policy:

|

|

Running the tests:

% conftest verify --report full

policy/gcp/bucket_force_destroy_tests.rego:

data.gcp_test.test_allow_create_bucket_with_force_destroy: PASS (926.401µs)

data.gcp_test.test_allow_empty_resource_changes: PASS (1.026078ms)

data.gcp_test.test_allow_update_bucket_with_force_destroy: PASS (857.508µs)

data.gcp_test.test_deny_delete_bucket_with_force_destroy: PASS (1.506513ms)

data.gcp_test.test_allow_delete_bucket_without_force_destroy: PASS (1.319212ms)

data.gcp_test.test_allow_delete_other_resource_type: PASS (1.329778ms)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PASS: 6/6What Doesn’t Work so Well

The following points are specific to the built-in OPA integration for Atlantis, which is what we currently use.

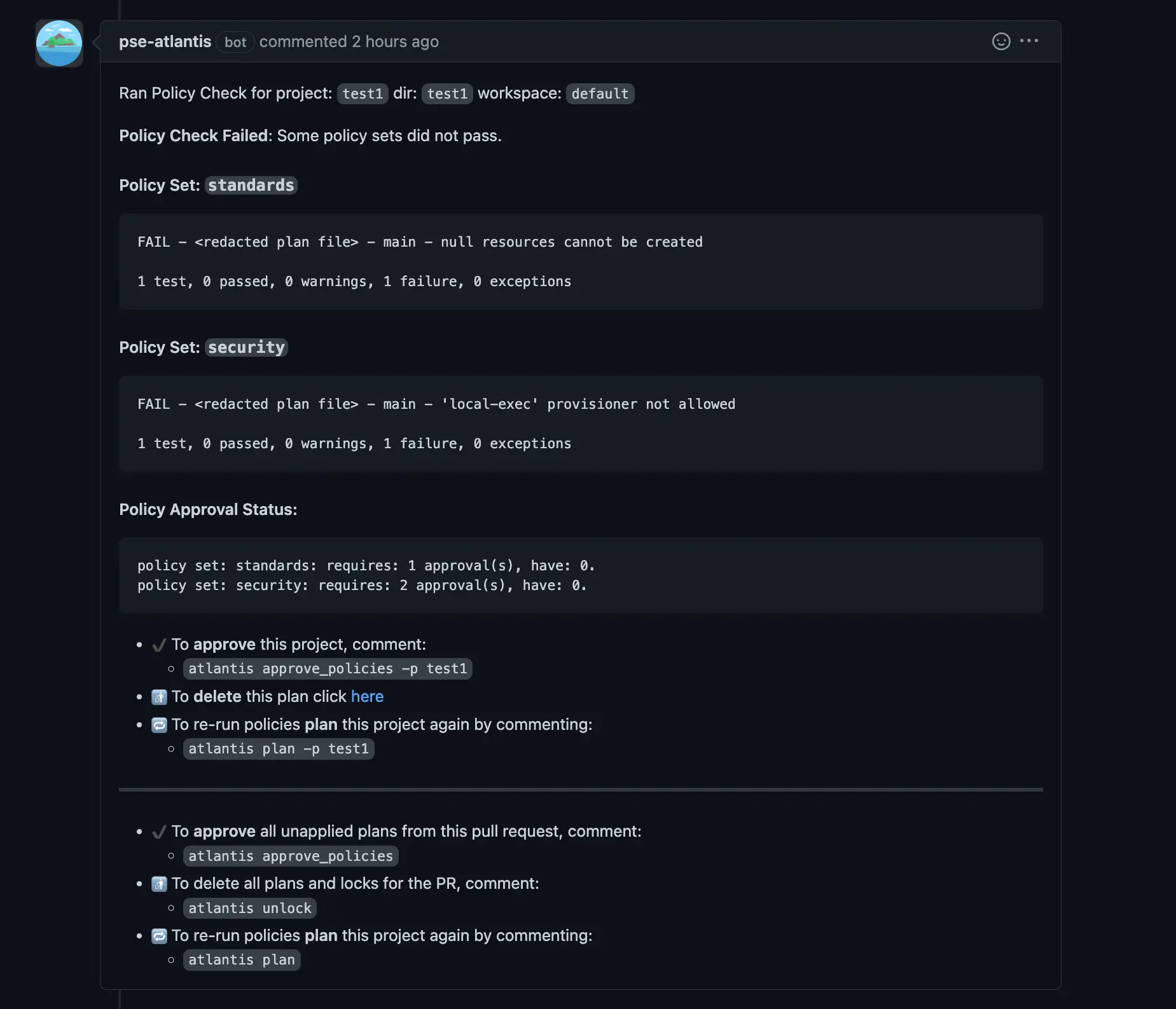

UX for Policy Violations

If you have a single policy set with a couple dozen policies and a single approver, the UX is good enough, but as your library of policies grow and you start separating them into different policy sets with different owners/approvers, the policy violation messages can get too long and confusing.

Policy violation notification as an Atlantis comment.

By default, this notification is also sent even when no policy violations are detected, increasing the comment noise in your PRs. To mitigate this, you can experiment with the server flag --quiet-policy-checks.

Workflow for Managing Policy Sets

Policy sets are configured via the Atlantis server-side repo configuration, which is a static configuration file:

|

|

It’s okay to start creating policies in a single set, but as you grow, you’ll likely need to assign different owners for different policy sets.

Also, depending on how frequently you update your policies, you might want to decouple the policy update workflow from the Atlantis server lifecycle. Conftest (and thus Atlantis) can fetch policies from a GitHub repository, OCI repository, etc, so use this to your advantage – but you need to be careful to sync disruptive changes (i.e. directory structure changes) to the Atlantis server-side repo configuration.

No Built-In Support for Policy Notifications

When a PR triggers one or more policy violations, all Atlantis does is create a comment in the PR. In our case, when that happens, the users themselves escalate to the SRE team for review or approval, but this might not work for you.

If you need other ways to be notified about policy violations (e.g. via Slack), you’ll need to implement it yourself.

One way could be writing a small GitHub App that receives hooks for all comments in a PR, detecting the policy violation comments, parsing/forwarding them to the owners via Slack, and maybe also providing actions directly in the notification for approval.4

Policy Approvals vs Branch Syncs

If you approve a policy for a branch that’s out of sync with the main branch, the policy approval will be “erased” after the rebase and you’ll have to approve it again, even when none of the code in the PR changes. This is particularly annoying for changes that require lots of back and forth due to apply errors.

If you want to resolve this, you’ll have to cook something yourself.

Again, some sort of GitHub App that automatically re-approves a PR that was once approved by some human as long as the set of violated policies and resources involved do not change.

Atlantis API

I once tried to enable the Atlantis API to implement basic drift detection and correction, but I could not make it work. Since the Atlantis primitives work on top of pull requests, even when using the API, you’ll need to provide a valid PR number when asking for a plan or apply, and even then things didn’t quite work as I expected.

Recommendations

- Let me repeat myself: lint and write tests for your policies!

- Add some unique identifier for each policy error (i.e.

GCP001); this would allow you to track the frequency each policy is being triggered, and maybe even provide a nice wiki for your users that explain each policy in detail, how to resolve the issue, etc. - Avoid putting too much stuff in the same file; keep each policy in a separate file.

- Periodically review your policies; check whether they are blocking stuff that needs to be blocked, or just introducing noise without real benefits; remove bad/useless policies.

- Be cautious when adopting third-party policy packs unless you have a way of granularly enabling or disabling specific policies that do not make sense for your own situation.

About the periodically reviewing your policies part: In one of the reviews, we identified that a single policy targeting a single resource accounted for 46% of all policy violation errors we had in the previous 90 days!

Conclusion

If you ask me if I think this is the dream workflow for Terraform code, I’d be lying if I said that it is. But hey, it’s open source, works mostly fine as long as you don’t want to do anything too crazy, and helped us a lot. I even made a contribution to the project a couple of years ago.

If my employer had deeper pockets, we might have gone in other directions, but I’m glad Atlantis exists. Now that the project was accepted into the CNCF, my hopes are up!

For those that use Atlantis and stumbled across some of these issues, I’d be happy to learn how you addressed them!

-

Terraform is a great tool, but not ideal as the go-to tool for development teams as it operates at a lower level. In the future we might explore tools like Crossplane, where we could build APIs based on abstractions that make sense for our own reality. ↩︎

-

Terraform modules are important tools for tasks like these, allowing you to ‘codify’ your organization’s standards directly as modules and reusing them where needed. In our case, we already had code managing cloud resources directly, so migrating everything to modules up front was too much work. With OPA, we could stop the bleeding by at least preventing the creation of new non-conformant resources and start getting value early in the process. ↩︎

-

This can work better or worse for your organization depending on a number of factors, such as the team maturity and the restrictiveness (or looseness) of your policies. You need periodic reviews to identify constantly breaking policies and fine-tune them for a better balance between noise and safety. ↩︎

-

That’s one of the things that we didn’t have the time to polish, being a small team with too much stuff on our plates. Maybe I’ll take a stab at this and publish as an open source project. ↩︎